In the lexicon of architecture, natural light in architecture is not just a tool or something that allows you to see; it is one of the fundamental design elements. Indeed, more than just brightness, natural daylight is the main material architects use to manipulate mood, define perception, and improve the utility of spaces. Architects use light as a vibrant, dynamic, and fluid medium to connect a structure to its environment. With skillful planning, light improves the quality of life for users, elevates the aesthetic of design, and impacts energy performance, transforming an unremarkable building into an emotionally responsive environment. Therefore, mastery of natural light is the hallmark of contemporary, human-centered design.

Why Natural Light in Architecture is Essential

The focus on daylight is deeply influenced by human biology and psychology. In fact, human bodies follow circadian rhythms, which are internal biological clocks primarily regulated by sunlight. Spaces that ignore this connection fail to provide sufficient daylight indoors.

Designers know that maximizing daylight elevates mood, boosts productivity, and increases comfort. Additionally, daylight exposure during the day helps regulate sleep rhythms at night, supporting occupant well-being.This concern aligns itself naturally with the concept of biophilia – our basic need to connect with nature. By framing views and pulling sunlight deep into the building, designers are able to support this essential connection making the building feel alive, rooted and restorative. Natural light becomes, therefore, not a feature, but a necessity to human wellbeing.

How Natural Light in Architecture Enhances Interior Spaces

The strategic use of daylight is the most cost-effective way to elevate a design’s aesthetics, creating a sense of luxury and depth that no artificial system can fully replicate.

Natural light has a special capacity to make any indoor space feel larger and airier. By eliminating dark corners and extending views outdoors, the room’s edges appear to recede. Furthermore, daylight creates shadows and depth, which add visual interest. As the sun moves, shifting patterns of light and shade highlight the building’s form and details.

Moreover, light showcases the inherent beauty of materials. For example, sunlight hitting a raw wood wall, an exposed stone wall, or polished concrete highlights the texture and tactile quality, turning any surface into a sculptural element. In addition, daylight makes colors appear truer, richer, and more natural than artificial bulbs, enhancing the quality of materials, finishes, and furnishings. Natural light establishes the standard for how well lit spaces can be. Natural light sets the standard for lighting quality—whether you’re designing a working kitchen, a warm living room, or a softly lit bedroom.

Techniques in Architecture to Maximize Natural Light

Architects ground the skillful use of light in a definitive awareness of the sun’s trajectory and a collection of sophisticated construction methodologies. Architects utilize a handful of fundamental strategies to manipulate, diffuse, and control light in their designs:

- Window Placement & Orientation: For instance, this technique places large glossy sections strategically to capture desirable light from the best direction. North-facing glass provides consistent cool light, while south-facing glass maximizes heat gain, which overhangs help moderate. Designers size and shape windows intentionally to control and moderate the beam of light, not just to provide a view.

- Skylights & Roof Openings: Skylights and roof openings provide essential light for single-story buildings and bring daylight to the center of large floor plates where lateral windows cannot reach. Skylights, clerestory windows, and light monitors bring vertical light down through the building, creating high levels of uniform brightness.

- Glass Walls & Large Glazing: Current structural possibilities facilitate almost seamless glass facades that optimize light penetration and create a slightly blurred threshold between the inside and outside yet visualize the interior space extending beyond normal limits. This is common place in 21st-century minimal designs.

- Light Wells & Courtyards: In densely built urban areas or large commercial buildings, architects carve light wells and interior courtyards thoughtfully from the building’s mass. Additionally, architects design vertical shafts and light wells to channel daylight and ventilation, especially to lower floors or interior-facing rooms.

- Reflective Surfaces & Materials: White walls, high-gloss surfaces, and polished floors amplify and redirect light. To enhance daylight, surfaces or materials such as reflective metals or special coatings can be placed adjacent to windows to reflect light further into a room.

Each of these techniques is a practical application of physics, strategically deployed to ensure that every part of the structure receives optimal, controlled illumination.

Balancing Light & Heat: The Design Challenge

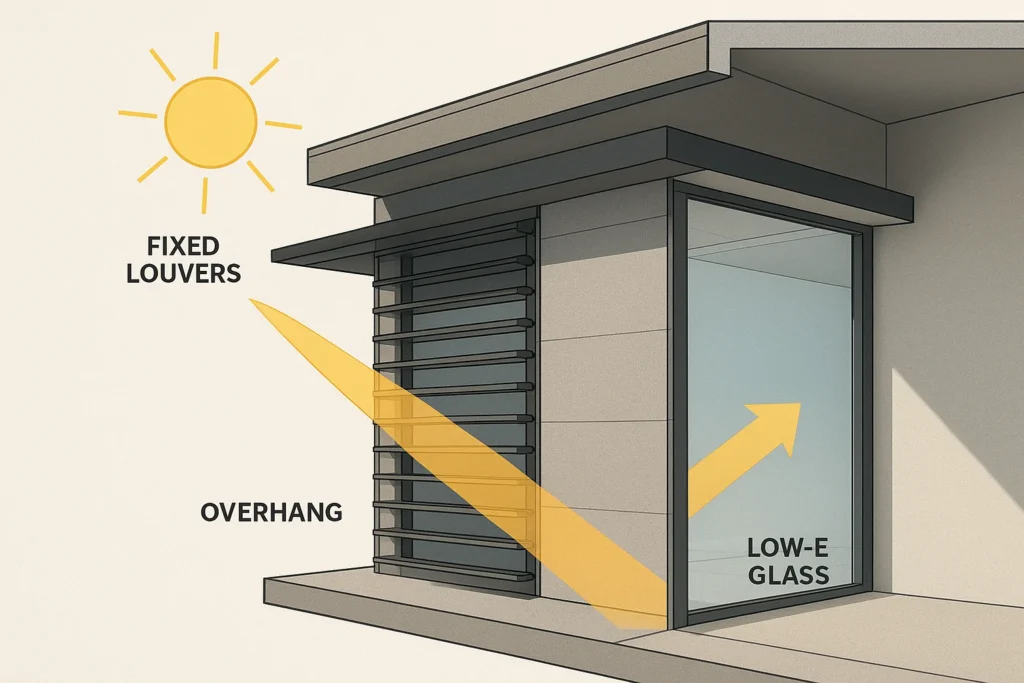

Although it is beneficial to maximize natural light, designers must address its side effects: glare and heating from excessive solar gain. For example, with large amounts of direct, unshaded sunshine, occupants can experience thermal comfort quickly, but they may also encounter uncomfortable visual hot spots.

Architects address this issue by distinguishing between diffuse sunlight, which they encourage, and direct sun rays, which can cause problems. Architects often use complex and costly methods to control sunlight. They install fixed louvers, exterior screens, or pergolas. These devices block the high-angle summer sun while allowing the lower-angle winter sun to enter the building. Moreover, material technology has improved remarkably in recent years. For example, Low-E (low-emissivity) glass lets visible light in while blocking infrared heat. This keeps interiors bright yet cool. It maintains comfortable temperatures without reducing brightness and positively affects the building’s thermal envelope.

Natural Light in Different Types of Spaces

Designers must tailor the application of natural light to meet the specific functional requirements of each building type.

- Homes: To improve and amplify the personal human experience, light in its natural state is used. For instance, in living rooms and kitchens, deep eaves over large south-facing windows create bright, functional spaces while preventing overheating. In the bedroom, light-filtering shades or north-facing windows provide a soft, consistent light. This creates a peaceful environment for waking up or relaxing in the evening. Comfort and ambiance is the goal.

- Offices: Light is improved for performance and thinking. Open floor plans use centralized lighting, wide shallow floor plates, and large windows to bring daylight to every desk. Additionally, designers use light shelves—horizontal surfaces near windows—to bounce light up to the ceiling. This helps distribute daylight to deeper parts of the space and improves visual comfort.

- Commercial Spaces (Retail/Galleries): Lighting creates dramatic effects and highlights products. For instance, retail spaces use directional spotlights to focus on displays and enhance natural light. Similarly, strict lighting control applies in galleries and museums. Designers sometimes install skylights with motorized blackout shades or UV-filtering diffusers. In addition, natural light can illuminate the gallery and provide ambient daylight. Designers must carefully manage it to protect sensitive art and artifacts.

Sustainability Benefits of natural light in architecture

A commitment to day-lit architecture is, at its core, a commitment to sustainability. By reducing reliance on electric light, buildings reduce energy use and energy costs significantly.

This reduces energy consumption and financially reduces energy expenses. A well-daylit space can delay turning on artificial lights until it gets dark, reducing energy consumption by up to 50%. This makes the building much more sustainable through sustainable use of fossil fuels used to generate electricity. Daylighting approaches often include passive design elements, such as operable windows that provide cross ventilation and fresh air. Combining daylighting with passive design reduces the need for mechanical cooling and improves the building’s sustainability performance.

Architectural Examples

All around the world, leading architects have consistently demonstrates that light can transform spaces. Scandinavian homes, known for their light-optimizing strategies, use minimal interior spaces and paint surfaces white to maximize limited southern sunlight. Contemporary glass homes maximize views while transforming their spatial layouts into complex light sculptures. Large commercial designs use soaring atriums. A central multi-story light well can transform even the densest office block into an inspiring shared space.

Conclusion

Natural light is more than a functional requirement. Architects use it as a creative tool and a key element in modern design. A careful incorporation or manipulation of natural light reveals meaning, adds beauty and contributes to the wellbeing of all users. Designers shift from sealed, artificial-light environments to healthy, responsive, and sustainable spaces. They prioritize methods that draw, diffuse, and control sunlight. Architecture is definitely light-forward, ensuring that human experience is a part of every design.

Architects consider how color and light affect interiors to enhance both mood and perception in a space.